Levi Garrison moved from Cumberland County, New Jersey, to Wheatfield Township in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania in the 1780s.

Westmoreland County was in Western Pennsylvania, on the western edge of the Allegheny Mountains. In the early decades of the nation, the county borders changed as newer counties were created when the populations grew. In the 1790s, most of the population of Pennsylvania lived east of the mountains. Today, the land that made up Wheatfield Township is part of Indiana County. It is situated in the Ligonier Valley and provided land for extensive grain farming.

Garrison appears on the tax lists for Cumberland County throughout the 1770s and is suspended from the Presbyterian Church in 1782 for becoming a Methodist.

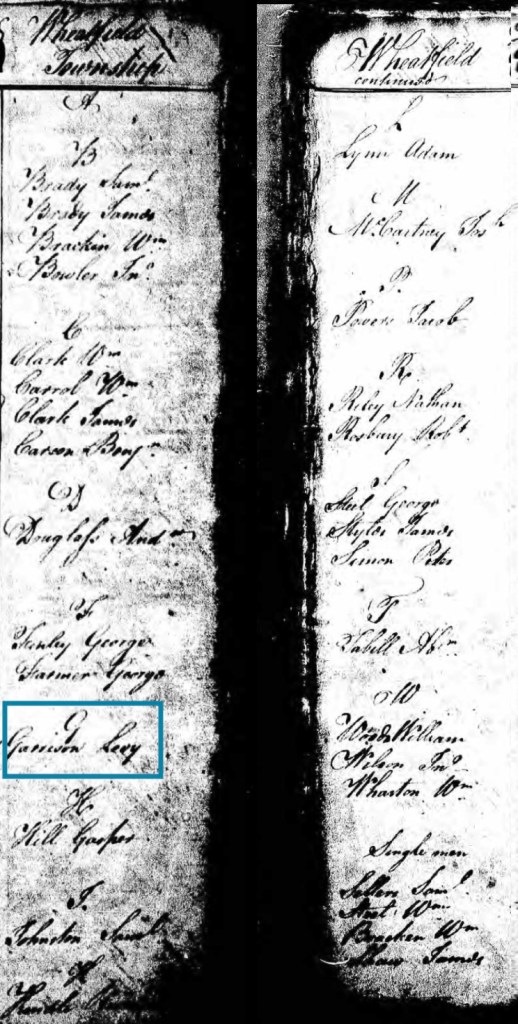

By 1786, Levi Garrison appears on the Pennsylvania Septennial Census for Wheatfield Township.

He appeared on the tax lists for the late 1780s. He had some land, some livestock and his property was usually valued in the middle to high range.

| Category | 1786 Tax List | 1787 Tax List | 1789 Tax List |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land | 300 Deed | 300 Improvements | 200 Warrant |

| Horses | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Cows | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Value | £136 | £65 | £41 |

Two facts suggests that Levi Garrison was a farmer. First, the majority of the population west of the Allegheny Mountains were farmers and he continued to acquire cows, likely used by him and his sons to plow the land and grow the wheat that his township was named for.

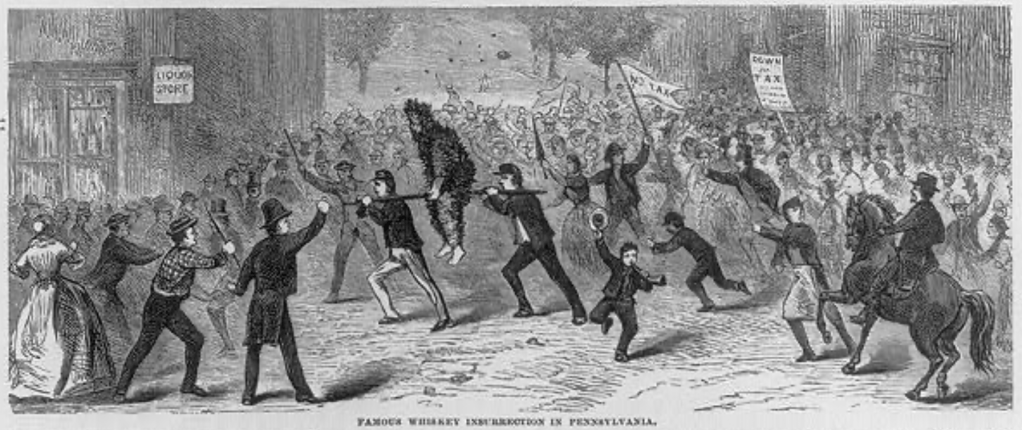

Whiskey Rebellion | 1791-1794

Sale of the wheat was not profitable if sold locally. However, converting the grain to whiskey and transporting east was more profitable because the distillery grain weighed less, took up less space and didn’t spoil. Additionally, as there was little cash in the western frontier, the whiskey was used as a currency. Western Pennsylvania produced 25% of the countries whiskey.

Therefore, when the federal government chose to issue an excise tax on whiskey in 1791 to pay for debts incurred during the Revolution ($25 million) and founding of the new nation, the farmers of western Pennsylvanian were angry.

The farmers of Western Pennsylvania took exception for multiple reasons. First, it was like taxing money itself, as the product was often used in lieu of cash. Second, because cash was rare, it was difficult to pay the tax as it was required to pay the tax in cash. Third, the tax was the same for both large and small distillers, meaning that small distillers had more of tax burden than larger distillers, and finally as the whiskey distillers were concentrated in Western Pennsylvania, one region was footing the repayment of the nation’s debts.

As a result, the farmers of Western Pennsylvania resisted the federal tax and harassed the local excise men, tarring and feathering like the colonists had done to British tax men.

The rebellion came to a head in 1794, when thousands of militiamen from Washington County, Fayette County, Allegheny and Fayette County came to Braddock’s field to openly rebel against the tax. Moderates were able to pacify the militia men, and even as Washington was leading troops to Western Pennsylvania, a battle was averted and the insurrection quelled.

Many of those participated in the rebellion moved west to avoid arrest.

It is unclear what role Levi Garrison played in the Whiskey Rebellion. From his tax lists, he had land and a sizable farm, suggesting that he had enough whiskey production that the tax’s burden was not a huge as it was on smaller distillers. Many of the militiamen were said to be landless and small distillers, and that larger landowners were moderates.

That said, in the 1790s, Garrison left Western Pennsylvania and moved to the Symmes Purchase in Ohio in 1798. Levi Garrison is in Hamilton County, Ohio in 1799, suggesting he was living in Pennsylvania in 1794. However, that would have been 4-5 years after the rebellion was squashed, suggesting he did not see the need to leave immediately.