Both pension applications for Michael and Peter Fulp describe their participation in the 1776 Cherokee Expedition. The Cherokee Expedition was the combined efforts of militias from multiple colonies to exterminate the Cherokee and open up land for Euro-American settlers.

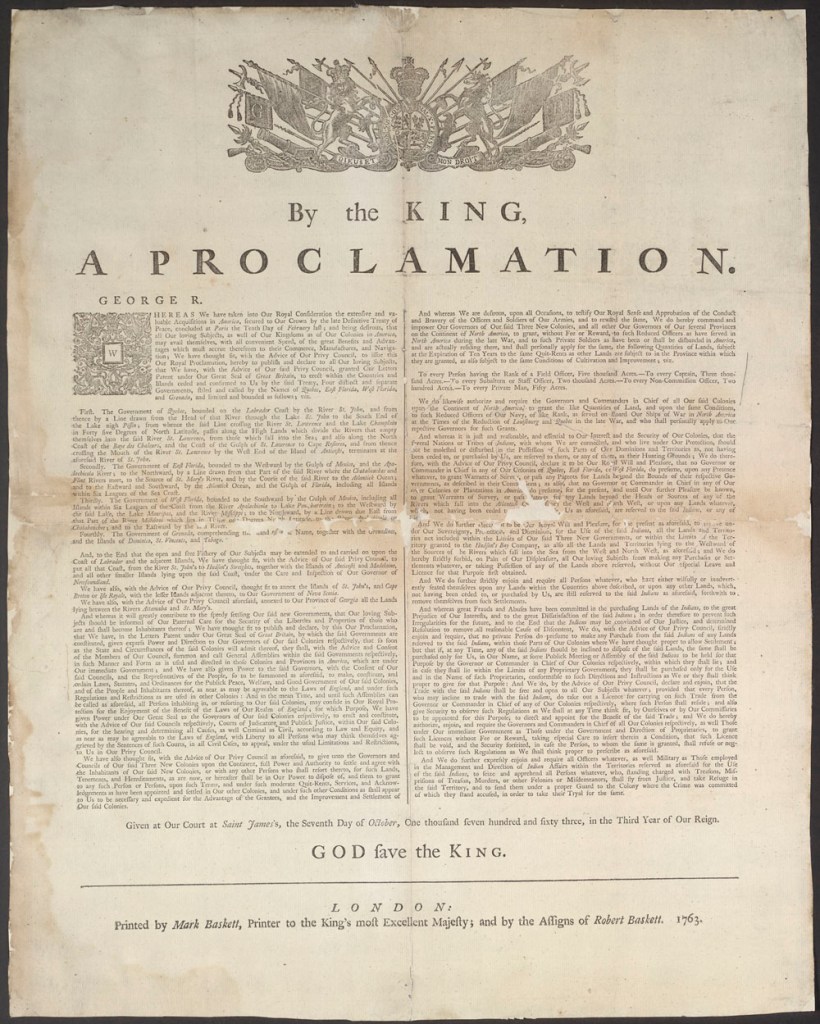

At the end of the Seven Years’ War (commonly known as the French and Indian War in the Americas), King George proclaimed the land west of the Appalachian Mountains as land reserved for Indian Nations and therefore off limits to Euro-Americans, upsetting settlers who sought land.

The Fulp family lived on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Appalachian, near the line of demarcation made by the King. As settlers illegally crossed into the “Indian Reserve” established by King George, the tribes resisted their intrusions with raids on the Euro-American settlements. The settlers came indifferent to the fact that they were settling on the farming and hunting lands used by the Cherokee.

Euro-Americans had settled in the Watauga, Nolichucky, and Holston river valleys in the late 1760s and early 1770s, in defiance of the King’s Proclamation. Settlers in the Watauga river valley created their own government separate from the British Crown. The King and his officials considered the settlements illegal. As the British officials tried to uphold the agreement between the Crown and the Indian Nations and allowed the Indian Nations to remove illegal settlers, the settlers saw the British as encouraging warfare between the Indians and the colonists. The 1836 map of the area shows the conquest of the region by the Euro-Americans with counties like Servier and Carter named after the Euro-Americans who was instrumental in the creation of Watauga settlement.

With the onset of the American Revolution, this created two fronts for the militias in the western backcountry. The tribes across the mountains as one front, and the British army in the east as the other front. As a result, the colonial leaders sought to rid the western front of Indian tribes. Militias from Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia joined on a united expedition. Col. Joseph Williams, writing of the expedition in the 1820s and from the settler-colonial perspective, justified the expedition, giving as an example: “The people who had settled on the Watauga and Holstein Rivers were compelled to abandon their houses and plantations and to seek safety in their forts and garrison”. He omitted that from the American Indian perspective, “We never thought the white man would come across the mountains, but he has, and has settled on Cherokee land. He will not leave us but a small spot to stand on. Should we not therefore run all risks, and incur all consequences rather than submit to further laceration of our country?” Indeed, Dragging Canoe, one of the leaders for the Cherokee tribes, felt that the only way to save his people from oblivion was to fight the Euro-Americans, while other Cherokee leaders tried to trade and negotiate peace.

The 1776 Map of the British Southern Colonies reveals no drawn western border for North Carolina which appears with Virginia to extend indefinitely west. Indeed, the Virginian and Carolinian surveyors were squabbling over the border in the west, with settlers unsure if they were in Virginia or North Carolina. The lands of the Cherokee are marked on the map, showing what would be called the Over Hill Towns..

Richard Caswell, the colonial victor at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge, and now the governor of the independent Carolina colony sent Col. Joseph Williams and others to support the expedition, among them Michael and Peter Fulp. A detailed description of the journey is outlined in both William’s memoir of the expedition as well in Michael Fulp’s application for a Revolutionary War petition.

(A general map of the southern British colonies in America: comprehending North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, with the neighbouring Indian countries, from the modern surveys of Engineer de Brahm, Capt. Collet, Mouzon, & others, and from the large hydrographical survey of the coasts of East and West Florida)

Williams, with his militia from Surry County, marched to join the Virginia militia. Both Williams and Michael Fulp recollect the start of the expedition. Williams wrote that it began in the month of September while Fulp does not recall the exact month, only that it was during “warm weather”. Both William and Fulp state that they marched to Flower Gap across the Blue Ridge Mountains. Williams wrote it as “Flour”, while Fulp’s application records it as “Flower Gap”. Today, there exists Flower Gap Road, immediately to the west of Cana, Virginia, just north of the Virginia/Carolina boundary, suggesting that the militia marched north and west from Surry County.

They crossed the New River, near Poplar Camp according to Fulp and at Herbert’s Ferry according to Williams, where they went to lead mines in Wythe County, Virginia. William Herbert, a Welshman, operated the lead mines, making shot, as well as the ferry on the New River. Apparently, Poplar Camp Creek Road led to Herbert’s Ferry.

On the other side of the river, they waited for a few days at Fort Chiswell before marching “slow marches” to the Long Island of the Holston River. Fort Chiswell was an outpost built during the Seven Years’ War at the junction of the Great Trading Path and the Richmond Road near New River. Long Island of the Holston river is located in what is modern-day Kingsport on the Holston River. The Long Island was a sacred council and treaty site for the Cherokee. And Euro-Americans had used it since the 1760s as a landmark for starting expeditions (e.g., Boone started clearing the Wilderness road from the Long Island in 1775; and the 1760s Timberlake Expedition used it as a starting place). The Long Island is likely what Fulp called the “Boat Yard” as it was a starting place for settlers moving west on the Tennessee River once the Revolution was over. Near here, the expedition built Fort Patrick Henry (name after the Virginia governor) and used it as a base for its forays into Cherokee Territory, suppressing resistance and eliminating food sources.

The march was slow for Euro-Americans who were traveling through a “wilderness” where there were “impenetrable” forests, with canes, bushes, brambles and briers. The Euro-American militias marched over 120 miles toward the Over Hill Towns of the Cherokee, coming to the French Broad River. Here, a Euro-American tried to negotiate peace on behalf of the Cherokee, however, the Col. Christian (the leader of the Virginia regiment, to whom Williams was joined) would not believe the treaty. Williams wrote, unironically, that “the answer [to consider peace] was dictated by a knowledge of the Indian character, and the insincerity of all their propositions of peace, unless when you have effected a complete conquest over them.” Williams, writing from the Euro-American perspective, failed to recognize how he and the others were protecting settlers who had ignored the terms of the Treaty of Paris and the Proclamation of 1763, and had invaded lands that were protected by a peace treaty.

Micheal Fulp wrote that they “marched in various directions till we reached home”. His description avoids detailing the scorched earth policy of the Euro-American militia which burned towns, crops, livestock and killed Cherokee people. Betsy Fulp, the wife of Peter Fulp, was succinct in her husband’s role in the expedition: “and the next service he entered a volunteer under the same Capt Goode in the summer of the same year 1776 and marched from Surry County aforesaid under Col. Williams and Major Winston to the Cherokee Nation of Indians and in which expedition he said he served four months.”

Both Peter and Michael Fulp died in Stokes County, North Carolina. Their children and grandchildren, however, migrated west into Claiborne County, Tennessee, past the Holston River.

Sources:

Williams, S. C. (1925). COL. JOSEPH WILLIAMS’ BATTALION IN CHRISTIAN’S CAMPAIGN. Tennessee Historical Magazine, 9(2), 102–114. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42637527

“A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776.” NMAI Magazine, http://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/demand-blood-cherokee-war-1776.