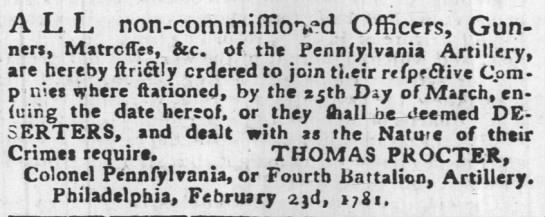

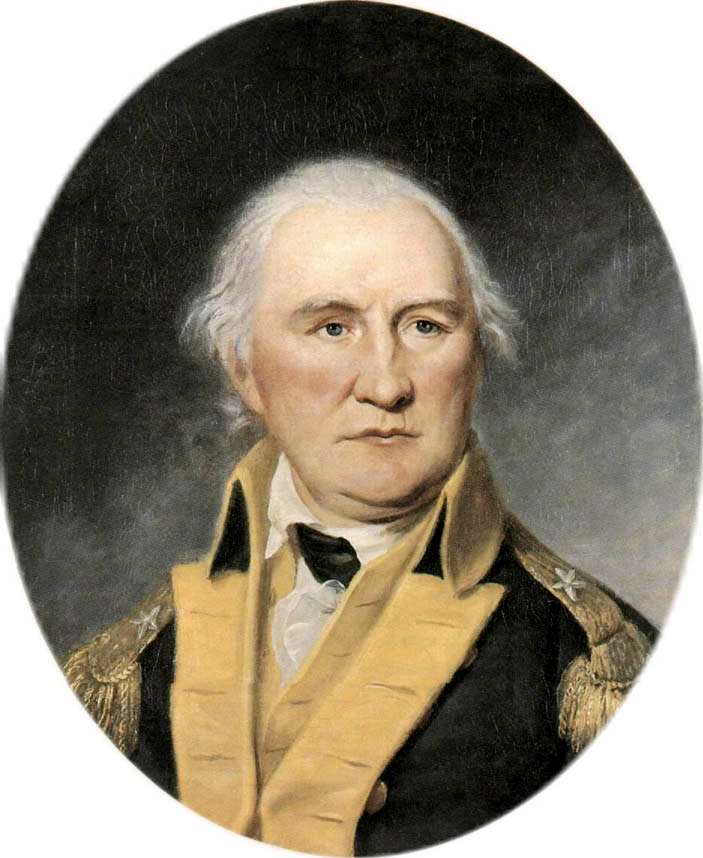

William Goff, a native of Ireland, who came to America during the colonial days preceding the Revolution, and during the war was employed by the government as a ship carpenter. Shortly after coming to this county, he married Prudence Passenger, a courageous colonial maid… John Goff [his son] was born in New Jersey previous to the time his family located to Hamilton County.

History of Franklin County, Indiana by August Jacob Reifdel

Some variation of this is told in multiple county histories for the great-grandchildren of William Goff: He emigrated from Ireland to New Jersey, married Prudence Passenger, served as a ship carpenter, and moved to Hamilton County, OH around 1804 where he lived his life as a farmer.

Many researchers have concluded from this that because William was an Irish Immigrant during the wave of Scots-Irish immigrants who came during the 1770s that he must have come from Ulster, a reasonable conclusion given that two-thirds of Irish immigrants during this time came from Ulster and were Presbyterians.

In contrast to this, I think it is reasonable to believe that he may have immigrated from Wexford County, Ireland, one of the southern colonies, and that he emigrated to join family members who had already established themselves in the colonies in the Upper Township area of the County of Cape May.

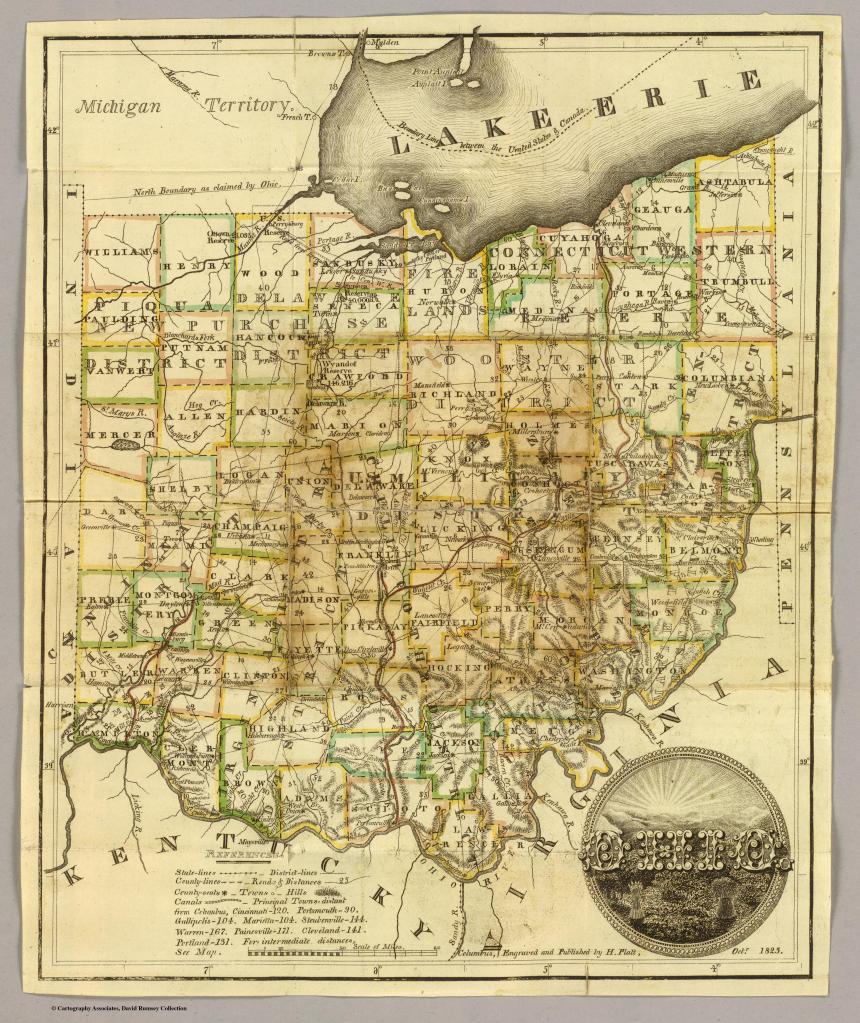

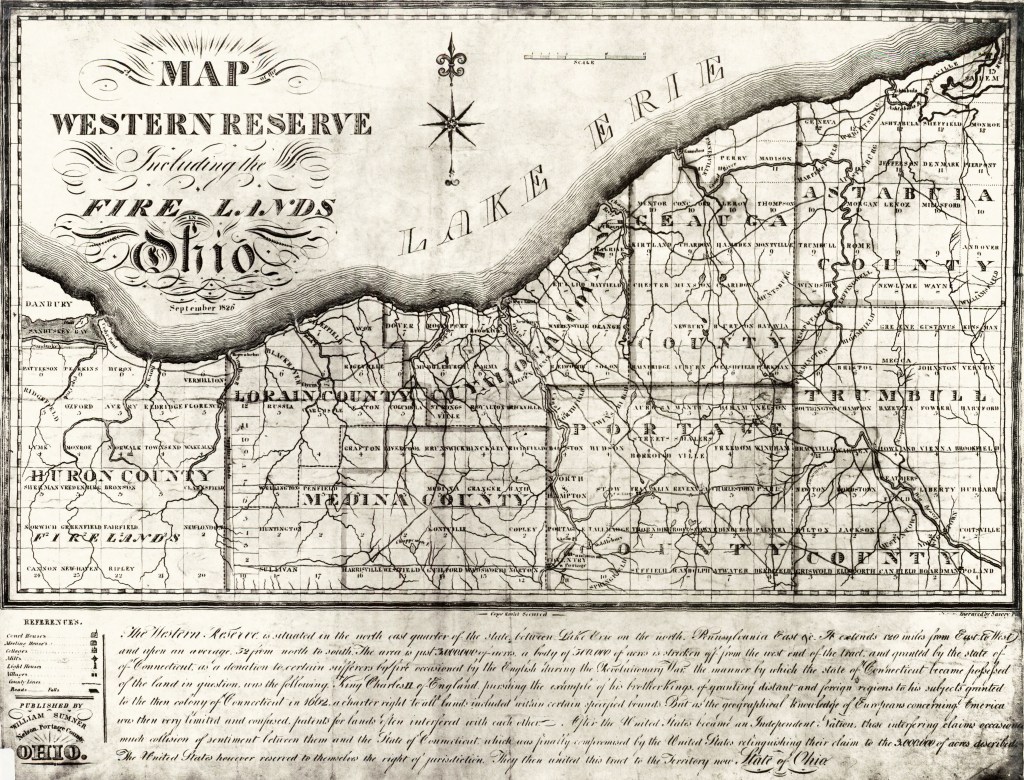

Evidence from Ohio

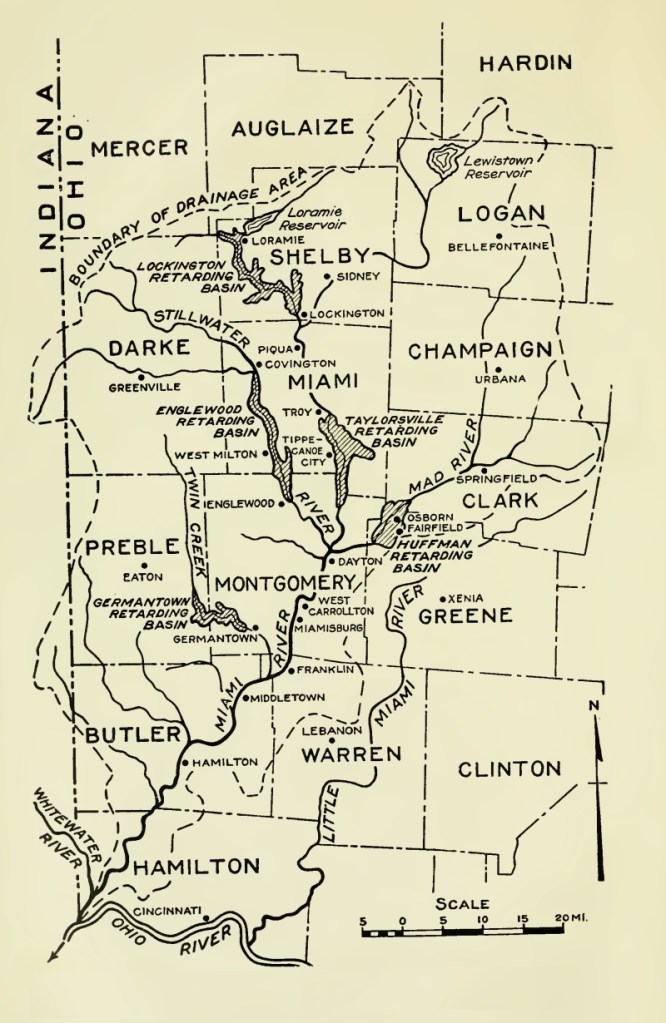

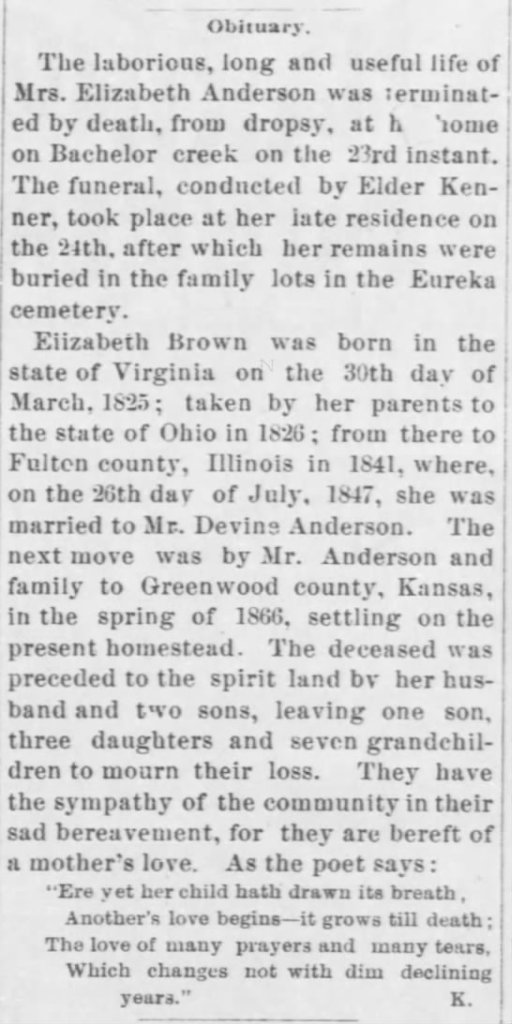

The histories of the counties in Ohio and Indiana state that William Goff immigrated from New Jersey to Ohio around 1804. He purchased land and settled as a farmer for the rest of his life. His son’s wife, Lucy(Johnson) Goff, raised sheep and flax to make clothing for the family and as a cottage industry.

The Deed Index for Hamilton County, Ohio lists William Goff purchasing land from D. Van Gilder (L 125) between the years of 1812-1814, the same years William Goff of Hamilton County, OH received a Credit Volume Patent for land purchased on credit from the US Government in Franklin County, IN. (hcgsohio.org; glorecords.blm.gov)

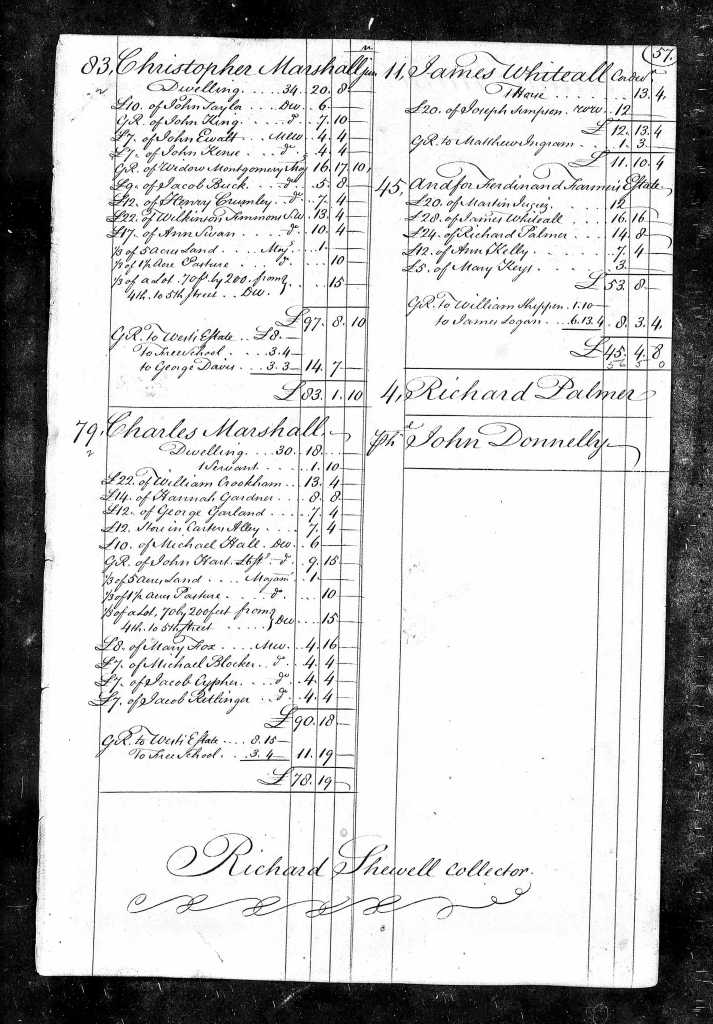

The name D. Van Gilder appears again in Ohio connected with William Goff. When Goff’s will was presented for probate in 1821, David Van Gilder and William Ruth served as witnesses as to the authenticity of the will, and in the 1820 Census, David Van Gilder is enumerated on the same page as William Goff, in close proximity. (ancestry.com)

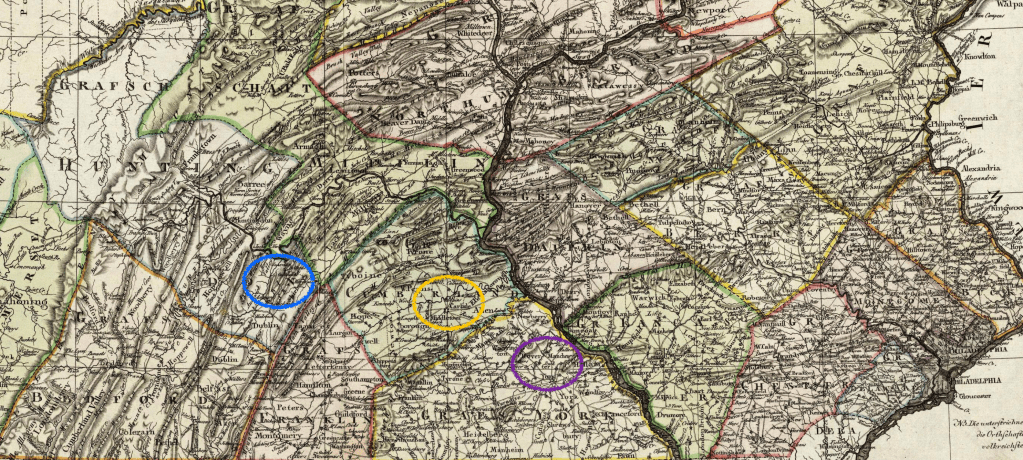

David Van Gilder was from Cape May County in New Jersey. He immigrated to Ohio around 1812, leaving behind the Upper Township of Cape May and Cedar Swamp. The Van Gilders were Dutch immigrants who had lived in Long Island prior to sailing to New Jersey in the mid-1700s and settling near Cedar Swamp near present-day Petersburg. (Source 1; Source 2)

Nearby, near the Tuckahoe River to the northwest, lived the Goff Family. In fact, both a John Goff and Isaac Vangilder witnessed a will that was probated in 1796 in County of Cape May, suggesting they were neighbor or relatives. Additional connections are suggested by the surnames of married couples. David Vangilder married Ann Shaw in 1795. Both Hannah Goff (1770) and Nathan Goff (1780), also married a Shaw, Thomas and Mary respectively.

Cape May, New Jersey

John Goff is the earliest recorded Goff in the County of Cape May (ear-mark in 1710) and it is likely that he immigrated with other families from Long Island and New England to Cape May. The Quaker families settled primarily the Upper Township area where the Goffs and the Van Gilders lived. A Friend’s Meeting House was established in Tuckahoe. Over the course of the 1700s, Quakerism declined and was replaced by Methodism.

The Goff family was one of the early converts to Methodism, converting in the 1770s; by the late 1790s, at least two Goffs were Methodist Ministers. In Ohio, John Goff, the son of William Goff, was an active Methodist, as well. (Source 1; Source 2; Source 3; Source 4)

The Biographical, Genealogical and Descriptive History of the First Congressional District of New Jersey details the family of David Goff, naming five sons, one of whom was “William, who went west”. In 1793, David Goff, Sr. will was presented for probate, and it details land given to him by an old mill and his brothers William, John, and David.

It is as likely possible that William was the “William who went west” and/or William arrived from Ireland to join the Goffs in Cape May, as a relative from the old country.

Irish Immigration

The article, Irish Immigration to the Delaware Valley before the American Revolution, describes Irish Immigrants as having easy access to seaports with established links between the Irish and the overseas locations through personal connections. This provided Irish Immigrants with a wealth information about prospective places for immigration. As such, it is likely that William Goff had connections with New Jersey prior to leaving Ireland and one likely connection was related Goffs who had had already settled in Cape May.

The Goffs in Cape May were part of a maritime economy that exported livestock and timber as well as the cottage industry of producing woolen mittens and stockings. Many of the men living in Cape May were full or part-time mariners. When either the British government (during the French and Indian War) or the American Continental Congress (during the Revolutionary War) hired privateers, many of the Cape May families invested in privateer ships and outfitted them for raids. This suggests that the Goffs were engaged in trade with connections to Ireland.

Which poses the question: where did William Goff sail from in Ireland? Did he sail from the north, where two-thirds of the immigrants said from? Ulster Presbyterians made up the bulk up of the immigrants to Pennsylvania in the year prior to the war. However, due to the connections with Cape May (Vangilden Family) and with the religious make-up of the county (Quakerism and Methodism), it seems more likely that William Goff came from a region of Ireland with tighter ties to Quakerism rather than Presbyterianism. The southern counties, Wexford and Waterford pop up in the 1850 Irish Surname Distribution map as a place where Goffs lived in Ireland and they pop up when the name Goff is searched in findmypast.com. Many of the records returned are from the Society of Friends.

This suggests that William Goff is not a Scots-Irish immigrant from Ulster, rather a Quaker/Methodist from the southern colonies of Ireland. His migration with the Vangilder family from Cape May, coupled with the connection to Methodism in both Cape May and the Northwest Territory suggests this alternate origin story.

Sources:

Ohio. Probate Court (Hamilton County); Wills, Vol 25-26, 1823-1884, ancestry.com

1820 U S Census; Colerain, Hamilton, Ohio; Page: 345; NARA Roll: M33_87; Image: 286, ancestry.com

Cape May County, New JerseyThe Making of an American Resort Community

History of the Ten Villages of Upper Township: Petersburg, Part 1

Biographical, Genealogical and Descriptive History of the First Congressional District of New Jersey

Geology of the County of Cape May of the State of New Jersey

The Cape May Navy: Delaware Bay Privateers in the American Revolution

Wokeck, Marianne S. “Irish Immigration to the Delaware Valley before the American Revolution.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, vol. 96C, no. 5, Royal Irish Academy, 1996, pp. 103–35, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25516172.